The Baron of Prestoungrange

Dr. Gordon Prestoungrange

Interview by Sarah Powel (part 2 of 3)

Prestoungrange yesterday and today

There is a surprising amount of historical information on the

barony and on the mixed fortunes of Prestoungrange and its owners,

and the area's history is well recounted in a series of booklets

Gordon is publishing at www.prestoungrange.org. The name Prestoungrange

derives from "Prestoun", meaning Priests' town and "Grange" denoting

a farm. The earliest owners derived their wealth from the local

wool, farming and coal mining industries.

Robert de Quincy, the first recorded owner, was descended from

Norman knights. In the twelfth century he was an important member

of the court circle of the Scottish King William I (The Lion).

Gordon relates that "de Quincy subsequently granted Prestoungrange

to Cistercian monks from Newbattle Abbey and the Order remained

there for four hundred years. The monks introduced salt panning,

hence the town's early name of Saltpreston, now Prestonpans. In

the early 16th-century, they built a nearby harbour, Newhaven,

which was successively renamed Acheson's and then Morrison's Haven.

This was the first important step in the development of the area

as a significant, international manufacturing and trading station

on the Forth.

"The monks' main goal in building the early harbour was to facilitate

exports of coal, salt and hides and also to provide a safe haven

for local fishermen. Prestoungrange is reputed to have been Scotland's

first coal mining area.

"At the Reformation, the 'Commendator', or administrator of the

Cistercian estate at Prestoungrange, Mark Ker, took possession

of the properties which were subsequently granted by the King

as the Barony of Newbattle, which included the lands of Prestoungrange.

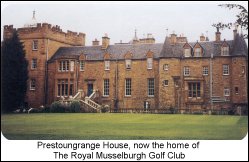

During Ker's tenure, a distinctively suggestive painted ceiling

was incorporated at the baronial home, Prestoungrange House, which

may, according to some contemporary theories, have been connected

to 16th-century practices of witchcraft. The ceiling was only

discovered - to some consternation - during renovation work in

1950 and has since been relocated to Merchiston Tower at Napier

University in Edinburgh.

"After the Ker family, who became the Earls of Lothian, several

other distinguished families held the lands and titles including

William Morison, Lord Prestoungrange, the Countess of Hyndford

and many generations of Grant Sutties. They all aided the development

of a range of secondary industries such as chemicals and soap,

glass, bricks and tiles, and pottery. The earliest sea-borne trade

from the port was with England, Holland and Sweden and this then

expanded to include the Baltic States, Germany, France, and Norway.

The harbour also brought in valuable additional revenue in the

form of dues.

"Robert Ker, the second Earl of Lothian, appears to have sold

the estates because of heavy debts. In 1624 he committed suicide,

beset by further debt - a not uncommon problem among the nobility

over the centuries. Prestoungrange House was then acquired by

the Morison family, in whose hands it remained for almost 150

years until debt - this time gambling was the cause - forced its

sale to William Grant in 1745 for the very substantial sum of

£Scottish 160,000.

"Prior to this William Morison had further developed the harbour,

renaming it as he did so. Trade was flourishing and, by the late

17th-century, as much as ten per cent of all Scotland's trade

with foreign ships passed through this port, and local fishermen

had moved on from their traditional catches to providing lobsters

and, particularly, oysters for Europe's nobility. Morrison's Haven

was also renowned for widespread smuggling and there were rumours

of secret passages to the beach from certain old houses in Prestonpans."

William Grant has been characterised as "an archetypal Scottish

Whig", a lawyer, supporter of the established Church, the

Union and the Hanoverian crown. He was also a Member of Parliament

from 1747 to 1754. By virtue of that office he played a significant

role in attending to matters in the aftermath of Bonnie Prince

Charlie's ill-fated attempt to reclaim the throne for the

Stuarts. Grant had the reputation locally for being rather

mean, although this might be unfair as he was known to be

supportive of the local development of industry and it was

he who established the manufacture of pottery. Exports of

Prestonpans "brownware" went to Europe, North America and

the West Indies.

On Grant's death his eldest daughter, the Countess of Hyndford,

inherited Prestoungrange, there being no sons. She took the

keenest interest in the farming activities undertaken there

and in her neighbouring baronies, especially Dolphinstoun

which is now held by Gordon's youngest son Julian. On her

death, it passed to her nephew Sir James Grant-Suttie and

his descendants. |

|

Initially, this family's ownership was marked by increasing wealth

and expansion of the estate, reflecting the key importance of

coal to the Industrial Revolution. However, in the late 19th-century,

family circumstances led to the estate being managed by outside

advisors which, combined with a drop in revenue from coal, led

to a decline in the family's fortunes. While the baronial house

remained in the Grant-Suttie's ownership until 1956, for many

years from 1909 it stood empty. Ironically, the proximity of the

collieries, which had for so long contributed to its owners' prosperity,

had become a liability making it unattractive to potential lessees.

In 1924 the property was finally let to the Royal Musselburgh

Golf Club (RMGC) which was seeking to move from its existing site

next to the Musselburgh Race Course. Some thirty years later the

house was put up for sale but the RMGC was unable to raise sufficient

funds to purchase it. The Coal Industry and Social Welfare Organisation

came to the rescue, buying the house and grounds on behalf of

the Musselburgh Miners' Charitable Society and enabling the RMGC,

almost half of whose members were from the mining community, to

remain there as a golfing sub-section of the society - a mutually

beneficial partnership that continues to this day.

|

The fortunes of the surrounding area have, however, continued

their decline. Gordon explains that "the harbour at Morrison's

Haven was badly silted up by the outbreak of the Second World

War, and was filled in with rubble and ash in the mid-1950s,

trade having been diverted to road and rail in the 1930s.

The coal mine closed in the early 1960s and the brickworks

ceased operation in the mid-1970s. Other traditional local

industries such as pottery and brewing have disappeared and

the local community has for too long now suffered the consequent

unemployment - such a transformation from its vibrant past." |

|