|

IN attempting in an earlier volume (The Temperance Problem

and Social Reform, 9th edition) to sum up the broad

conclusions to which their investigations had led, the present

writers endeavoured to concentrate attention upon a few

important points which they believe to be fundamental in

any effort to solve the problem of intemperance.

For the convenience of those who have not access to the

last edition of the earlier volume, and to prevent misunderstanding,

the summary there given is now appended:

1. Summary of leading propositions on which legislation

should be based

The propositions which we have attempted to establish are

chiefly these:

(a) That the present consumption of intoxicants in this

country is not only excessive, but also seriously subversive

of the economic and moral progress of the nation.

(6) That the enormous political influence wielded, directly

and indirectly, by those interested in the drink traffic,

threatens to introduce "an era of demoralisation in

British politics," and that this menace to the independence

of Parliament and to the purity of municipal life can only

be removed by taking the retail drink trade out of private

hands.

(c) That when the retail trade is taken out of private

hands, regulations for its conduct can be quickly adapted

to the special needs of each locality, and reforms now difficult

to attain, such as Sunday closing, reduction in the number

of licensed houses, the shortening of the hours of sale,

the non-serving of children and of recognised inebriates

will then become easy of accomplishment.

(d) That in the present state of public opinion the adoption

of prohibition in the large towns is to be regarded as impracticable,

although it is possible that local veto might be successfully

exercised in a suburb, or ward, of a town.

(e) That in no English-speaking country has the problem

of the intemperance of large towns been solved.

(/) That an examination of the causes of alcoholic intemperance

shows us that, whilst some of these are beyond our reach,

others that are of the utmost importance are distinctly

within the sphere of legislative influence.

(g) That we must recognise as among the chief causes of

intemperance the monotony and dulness—too often the

actual misery—of many lives, coupled with the absence

of adequate provision for social intercourse and healthful

recreation.

(h) That it is unreasonable to expect to withdraw men from

the public-house unless other facilities for cheerful social

intercourse are afforded. Such counteracting agencies, to

be effective, will cost a great sum—estimated by the

present writers at £4,000,000 per annum.

(i) That this sum can be easily obtained if the retail

trade is taken out of private hands, but that it is not

likely that the necessary funds will be furnished either

from municipal taxation or the national revenue.

2. The proposed lines of action and how to safeguard

them

A careful attempt has been made to frame practical proposals

in harmony with the foregoing propositions. The proposals

made frankly recognise : First, that reforms to be effective

must be constructive as well as restrictive. Secondly, that

they should reach as far as the progressive spirit of the

community will allow, and should be consistent with further

advance. Thirdly, that they should educate and set free

the latent progressive resources of each locality.

The present writers are well aware that objection has been

taken to schemes for the municipalisation of the drink traffic,

on the ground of the possible danger of the trade being

run for profit in order to reduce the rates. This danger

is, however, not merely remote from, but absolutely destroyed

by, the present proposals.

These proposals provide for a system of local restriction

and control from which all that is commonly objected to

in schemes for public management has been effectually and

of set purpose excluded.("I have argued for years

against every form of municipalisation. I have denounced

it in a hundred towns. But Messrs. Rowntree and Sherwell's

scheme has met all the objections which I have ever urged,

and for the first time we are presented with a plan which

the sworn prohibitionist can adopt without compromise of

deep conviction and without fear of ultimate danger and

loss."—REV. C. F. AKED, Paper read at th«

National Council of Free Churches, March, 1900.)

It is provided:

(a) That localities shall have permissive powers to organise

and control the retail traffic in liquor either directly

through the municipal council or through a company (as in

Norway), but always under the direct supervision of the

central government and only within clearly defined statutory

limits.

(b) That the whole of the profits shall be handed over

to a central State Authority for disbursement, the first

charge upon such profits to be the provision and maintenance

of adequate counter-attractions to the public-house, the

balance of the profits being pni-.l into the national exchequer.(In

any scheme for the disbursement of profits regard would

of course be had to necessary appropriations for sinking-funds,

etc. )

(c) That the sole benefit which a locality shall receive

from the profits of the traffic shall be an annual grant

from the State Authority for the establishment and maintenance

of recreative centres, the primary object of which shall

be to counteract the influence of the drink traffic—

such grant to be a fixed sum in ratio to population and

not in ratio to profits earned.

(d) That similar grants shall be made to prohibition areas,

all inducement to continue the traffic for the sake of the

grants being thus effectually destroyed.

(e) That where municipal councils adopt the system and

elect to control the traffic, they shall, as in the case

of the present technical education committees, invite the

active co-operation of a fixed number of influential citizens,

other than members of the council, in the work of local

management. (That the scheme, in its provision of recreative

agencies, would require for its full success the active

co-operation in each locality of earnest citizens is certain.

But the experience of School Boards especially has shown

that there is no lack of high-minded and gifted men and

women willing to devote time and labour to well-devised

schemes of social service.)

(f) Finally, the right of prohibiting the traffic is placed

within the power of every locality.

It is evident, therefore, that the conditions would be

such as to destroy the risk of municipal corruption. That

the scheme, by enlarging and enriching the idea of municipal

responsibility, would have an entirely opposite effect could,

with equal explicitness, be shown. As Lord Eosebery has

admirably put it: " The larger the sense of municipal

responsibility which prevails, the more it reacts on the

corporation or the municipality itself. By that I mean this,

that the men outside the municipality, or who have hitherto

held aloof from municipal government, when they see the

higher aims of which the municipality is capable, when they

see the wider work that lies before it, when they see the

incomparable practical purposes to which the municipality

may lend its great power, are not inclined any longer to

hold aloof." (Glasgow Herald, January 24th, 1898.

)

3. How the scheme could be carried out

But it may be asked, How is this scheme to be carried out

? What obstacles stand in the way of its adoption ? There

can be but one reply. It is the question of compensation

that blocks the way to all far-reaching temperance reforms.

Neither the proposals advocated in this chapter, nor local

veto, nor any other important scheme of reform, can be carried

out until the question of compensation has been settled.

The present writers believe that this settlement must be

effected upon the basis of a national time-notice. On this

ground, therefore, if on no other, it would seem eminently

wise for all practical temperance reformers to endeavour

to secure legislation upon the lines of Lord Peel's Report,

so that at the end of the time-notice " no compensation

of any kind would be given, and . . . the field would be

clear for any further legislation, experimental or otherwise,

which Parliament might be disposed to enact." (Minority

Report of the Royal Commission on Liquor Licensing Laws,

p. 270.)

Supposing, then, the time-notice to have expired, what

are the localities to do ?

The alternatives which would be open to them would, broadly

speaking, be as follow:

1. They might continue the present system of private licence,

either with or without high licence in some one of its forms.

2. They might adopt prohibition.

3. They might take the trade out of private hands and introduce

a system of local restriction and control, to be exercised

by either

(a) A disinterested company, or (b) The municipality.

It is with the third of these alternatives only that we

are at this point concerned.

(a) If it were proposed that local control should be exercised

through a company, as in Norway, a body of resident citizens

organised, or ready to be organised, as a company, would

make application to the licensing authority to take over

for a specified term of years (The period would coincide

with the period allowed by law for the recurrence of a prohibition

vote.) the whole of the retail licences in the place,

undertaking that the shareholders should not receive more

than the current rate of interest (as defined by law) and

further undertaking that all conditions attached by the

licensing authority to the licences should be carried out.

If more than one company applied, it would be for the licensing

authority to determine which body would be most likely to

carry on the work of effective control with disinterested

intelligence.

If the licensing authority declined all applications from

companies, then the inhabitants of the place could by a

popular vote compel the adoption of the Company system at

the first subsequent issue of licences.

(b) If a municipal council desired to work the controlling

system by taking the traffic into its own hands, it could

do so by formal resolution. But if a municipal council was

unwilling to take the initiative, or the licensing authority

to sanction the application, then the inhabitants of the

locality could by popular vote compel the adoption of the

system at the first subsequent issue of licences.

Local control, whether exercised by a company or by a municipality,

would of course be carried on in conformity with the requirements

of the central government, to whom all profits would be

handed over for disbursement.

4. The limited alternatives open to temperance reformers

It is well to remember that the alternatives open to temperance

reformers are very few. There is a growing feeling that

the enormous monoply profits which at present attach to

the Trade, and which must grow, rather than diminish, with

an increasing population and a diminishing number of licences,

ought not to be reaped by private individuals, but be used

for the benefit of the community. The question to be decided

is, How best may this be effected ? One method of effecting

it is by allotting the licences to those who tender the

highest licence fees, or—if this method be objected

to—by largely increasing the statutory fees; in other

words, by adopting, in one or other of its forms, a system

of High Licence.

But apart from the fact that this suggestion touches part

of the problem only, its defects, as we have seen, are obvious.

It not only fails to destroy the political influence of

the Trade, but it gives the licensee an even greater incentive

to push his sales. The increased cost of his licence must

be met by increased sales.

Where prohibition is impossible, the only alternative scheme

to private licence is to take the traffic out of private

hands. This can be done either as in Russia, by a system

of State monopoly, or by a system of local restriction and

control as proposed in this chapter. The former system is

clearly inadmissible. Its defects are too obvious to call

for further comment. We are therefore shut down to some

such scheme as is here proposed— a scheme of local

management carried out under strict statutory safeguards.

This being so, the only remaining question to be decided

is the appropriation of the profits. Here again the alternatives

are simple and clearly defined. The profits might be devoted

to (a) the relief of local rates; (b) the subvention of

local charities, as, until recently, in Norway ; (c) State

or Imperial purposes; or (d) the provision—as is here

suggested—of efficient counter-attractions. The first

of these alternatives is so inherently vicious, and would

encounter such overwhelming opposition, that it need not

be further considered. The second and third proposals, although

far less objectionable, are still open to serious criticism.

Their inherent defect is that they would deflect and absorb,

for quite other purposes, resources that are needed for

directly combating the evils of the traffic. The fourth

alternative is free from these defects. It starts from the

position, which few will question, that the public-house

problem is largely—by no means entirely— an "

entertainment of the people " problem ; that it has

its roots in ordinary social instincts as well as in depraved

and unenlightened tastes; and that it can only be effectively

solved when provision is made for adequate counter - attractions.

It is claimed for the present proposals that they make such

provision possible in a form that would powerfully contribute

to the highest interests of the individual and the truest

progress of the State.

(An objection is sometimes taken against municipal or

company control on the ground that it would involve the

community in complicity with a demoralising traffic. The

responsibility, however, is one that already exists. At

the present time both our national and local exchequers

are directly and substantially recruited from the proceeds

of the sale of intoxicants. Not only is a vast sum, amounting

to thirty-four millions sterling (or nearly one-third of

our entire national revenue), annually appropriated to national

purposes from Customs and Excise duties on alcoholic liquors,

but a further sum of two millions, annually raised from

licence fees, is applied to local purposes in direct relief

of rates ; while a still further sum of one and a half million,

derived from additional taxes on liquor, is allotted to

local councils, chiefly in support of technical instruction.

To add to these vast sums (or any remnant of them) the further

sums represented by the profits on such sales as must for

the present continue, is not therefore to introduce a new

principle, or to create a complicity which does not already

exist. To take a single illustration: Leeds already receives

from its liquor licences, in direct relief of local taxation,

an annual sum of £15,000, together with a further

sum of £7,000 representing its share of the special

duties on beer and spirits imposed by Mr. (}oschon in 1890

and subsequently allotted to local councils in support

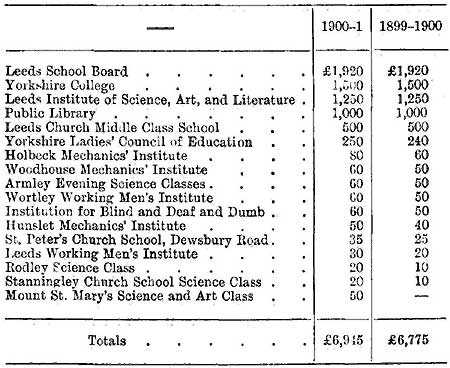

of technical instruction, etc. The use which Leeds has made

of this latter sum in the last two years is shown in the

following table:

To the extent of £22,000 per annum, therefore,

Leeds has at the present time a direct complicity in the

liquor traffic in its midst.

To allot to Leeds, as is here proposed, an annual grant

out of the aggregate national profits of the liquor traffic,

for the maintenance of effective counter-attractions to

the public-house, is not, therefore, to create a complicity.

The complicity exists already. Moreover, it must continue

to exist under any conceivable licensing system. The only

way to eradicate complicity in the liquor traffic would

be to abolish all licences and all Customs and Excise duties

on liquor, and to throw open the traffic to anyone who chose

to engage in it—a proposal that is manifestly utterly

impracticable.

But the question is really a practical one. We are all

agreed that for some time to come a considerable volume

of trade in alcoholic liquors will continue. Is it better

that it should continue under a system which aggravates

the evils of the traffic and produces the maximum amount

of social demoralisation and loss, or under conditions of

restriction and control which reduce the evil effects of

the traffic to a minimum ?

As Lady Henry Somerset, in discussing the present proposals

(Contemporary Review, October, 1899), pertinently asks:

"Are we to be regarded as ' having complicity' with

a trade for the reason that when we cannot suppress it altogether

we desire so to change its form and character that we deprive

it of three-fourths of its power to harm, but permit a fourth

of that evil to continue for a time 1 I hold that it is

our duty to restrict the evil as far as we can, and I hold

that we are responsible only for the amount of harm which

we could prevent, but allow to continue." )

5. Final appeal

The final appeal may be made in the eloquent words with

which, twenty years ago, the Lords' Committee on Intemperance

summed up the argument for local management and control.

Referring to the objections urged against both the Gothenburg

system and the system of direct municipal control, the Committee

say : " We do not wish to undervalue the force of these

objections; but if the risks be considerable, so are the

expected advantages. And when great communities, deeply

sensible of the miseries caused by intemperance, witnesses

of the crime and pauperism which directly spring from it,

conscious of the contamination to which their younger citizens

are exposed, watching with grave anxiety the growth of female

intemperance on a scale so vast and at a rate of progression

so rapid as to constitute a new reproach and danger, believing

that not only the morality of their citizens, but their

commercial prosperity, is dependent upon the diminution

of these evils, seeing also that all that general legislation

has been hitherto able to effect has been some improvement

in public order, while it has been powerless to produce

any perceptible decrease of intemperance, it would seem

somewhat hard, when such communities are willing, at their

own cost and hazard, to grapple with the difficulty and

undertake their own purification, that the Legislature should

refuse to create for them the necessary machinery, or to

entrust them with the requisite powers." (Report

of the Lords' Committee on Intemperance, 1879, p. 25. )

The reasonableness of this appeal will probably be generally

accepted, and its force may justly be claimed in behalf

of the present proposals. That these proposals would solve,

absolutely and definitively, the entire problem of intemperance,

is neither claimed nor believed. This no single scheme can

effect. But that they offer a reasonable basis for co-operation

to all who are concerned to achieve such a result, and would

powerfully contribute to bring it about, is fully and earnestly

believed. If the proposals fall short of the full aim of

the idealist, they in no way conflict with his ideal; they

simply lay the foundations upon which he and others may

build.

NOTE.—The wide acceptance of the leading principles

and practical proposals outlined above is indicated by the

opinions which follow - Some Personal

Opinions.

|